Lesson 4 – Effective Communication and Scientific Writing

All lectures will be delivered as readings that you complete on your own time. Post questions with the lesson on Piazza.

Make sure to read this article before moving on to Methodology Assignment 2, which is due on Tuesday, October 31st. In addition, this article will be crucial in writing the report (and its checkpoint) for your Quarter 1 Project.

Remember, the Quarter 1 Project Checkpoint is due on Monday, November 4th. The report part of your checkpoint submission will consist of the title, abstract, and introduction of your Quarter 1 Project. These components are discussed in more detail below.

Table of contents

- Overview

- Effective Communication

- Goals of Scientific Writing

- Guidelines

- Anatomy of a Scientific Paper

- Exercises

Overview

The standards for effective written communication vary by domain. Your domain should have an example of a scientific paper (henceforth, just “paper”) that models best practices.

- If your Quarter 1 Project involves replicating a paper, that paper is your example.

- If, instead, your Quarter 1 Project consists of completing tasks from several papers, choose one of the papers that you’ve read in your domain.

If it’s not clear which paper you’re meant to use as an example, you can ask your mentor:

When writing the reports for our Quarter 1 Project and Quarter 2 Project, we are supposed to follow the style of a paper in our area. What paper should we use?

As you read through this lecture, you should try and map the principles discussed to the example paper in your domain. Not all of the nitty-gritty details discussed here will apply to every domain, but the high-level ideas will.

Note: The principles discussed here will be used to evaluate your project reports throughout the rest of the capstone!

Effective Communication

Before looking at scientific papers specifically, it’s worth thinking about how to communicate effectively with different audiences more generally, regardless of the medium. Regardless of the audience, here are some general principles you should follow:

- Be as specific as possible. Vagueness causes confusion. Use concrete and testable terms, and refrain from using adjectives and adverbs. (For instance, instead of saying “Our classifier is much more accurate than the previous state-of-the-art model on similar tasks” , say “Our classifer achieves a testing accuracy of 84% on TritonDataset, higher than the previous record set by TritonModel of 81%.”)

- Avoid unnecessary terminology and the curse of knowledge. That is, define and explain concepts in plain English so that other data science majors outside of your domain and hiring managers at your dream company can understand what you did and why it’s relevant. After writing a report, website, or poster, step aside and try to unlearn the things you already know. Then, approach the draft again with a fresh pair of eyes – more often than not, you will find blindspots of your earlier self.

- Try to tell a story! Regardless of the platform, you are telling a story about your data. Stories are easier to follow if you have a main argument. Decide what is the central dramatic argument of your delivery. Have a strand of arguments that lead to the main point if it is complicated. Spend more time on the parts of your analyses that are interesting, and quickly cover the parts that are uninteresting (but still report them).

Watch the video below, prepared by HDSI and Bioengineering Professor Benjamin Smarr. Professor Smarr is a member of HDSI’s Industry Board, where he frequently meets with data scientists and engineers from industry. They tell him that the most common skill they see candidates from the DSC program lack is not technical skills, but rather, the ability to communicate their technical ideas effectively. As such, he often teaches a course called “Hardening DSC with Soft Skills”, in which he equips students with the communication skills they need to succeed in the real world. The video below synthesizes the key ideas in his course.

After watching the video, complete Methodology Assignment 2, which will ask you to reflect on what you’ve learned.

The rest of this article discusses how to structure papers specifically, though the ideas discussed in the video are still relevant, as they will be when it comes time to present your Quarter 2 Project to a live audience at the capstone showcase this upcoming March.

Goals of Scientific Writing

Papers are structured differently than, say, books, blog posts, and lectures. Papers are structured in a way that makes it easy for readers with different backgrounds to easily:

- Determine if the paper will be of interest to them.

- Read about just the parts of the project described in the paper that are relevant to them.

While the names and details of sections in a paper will vary depending on the publishing venue and domain, all papers consist of the same three key components (borrowed from this meta-paper that you should also read):

- Context: At the start of the paper, there is a brief description of what problem is addressed in the paper, why that problem is interesting, and why the authors’ approach is different. The goal of this section is to help potential readers determine if this paper is worth reading for them (and convince them to read it).

- Content: What the authors did to solve the problem at hand.

- Conclusion: The key takeaways and impacts of the results. Here, authors convince the reader why their work is meaningful.

When you’re looking for relevant background reading for a project – both now and in the future – what you’ll typically do is skim through the abstracts of several papers. If the abstract of a paper seems relevant, you may read the conclusion section. If the takeaways in the conclusion seem relevant to your project, you may then choose to read the bulk of the paper to see how the authors executed their project to see if there’s anything you can adapt and extend. By writing about their work in this rigid structure, authors help others understand what exactly was accomplished by their project.

Guidelines

When writing a paper, follow these guidelines.

- A paper is a narrative essay that describes a problem, methods to solve the problem, and the results of the approach.

- In this lecture, the project descriptions, and potentially in your weekly participation questions, you are given questions that your paper should answer. However, your paper should not read as if it’s a bunch of answers to pre-canned questions back-to-back – it really should feel like a story.

- The narrative that your paper follows should be about the methods and results, not an autobiography of your project and how you worked on it. Every project produces work that is irrelevant to the results; do not discuss irrelevant work in your paper.

- Figures (tables and graphs) should be self-contained and complete. In fact, you should strive to create figures such that readers can understand the high-level takeaways of your paper just by looking at the figures.

- To ensure that you’re working towards this goal, make sure to give each figure an appropriate title, axis labels, and captions.

- Keep in mind that you will know your work much better than almost anyone else who will ever read it; make sure to be careful to include all necessary details and not make assumptions about what the reader knows about your project.

- Cite others’ work frequently. Learning from and using others’ research is something to be proud of! However, don’t throw in a bunch of citations just to have them – only discuss and cite work that’s relevant.

- Only include statements that are verifiably correct. If a statement is a hypothesis or opinion, make that clear.

- As far as language goes:

- Use the active voice with first person plural (“we”) to refer to both the author(s) and the reader.

- Use the simplest language needed to convey your message; don’t use fancy jargon unnecessarily. Make sure to always define acronyms the first time you use them, as well as any project and domain-specific terms that may not be common knowledge.

- Try to quantify as much as possible, rather than using flowery adjectives and adverbs like “very” and “large.” Stating that your new method led to a “very large” improvement in accuracy over a previous method doesn’t mean anything to someone who is unfamiliar with your work – instead, state what the actual improvement is. It’s important to be specific, as vague statements contribute nothing.

Anatomy of a Scientific Paper

As mentioned earlier, the titles of sections in a paper may vary between publication venues and disciplines. However, most papers will contain the following sections in some form:

| Section | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Abstract | What did we do? |

| Introduction | What is the problem? |

| Methods | How did we approach it? |

| Results | What did we find? |

| Discussion | What did it mean? |

| References | Who did we cite? |

| Appendix | Details (particularly those that disrupt the narrative flow of the paper) |

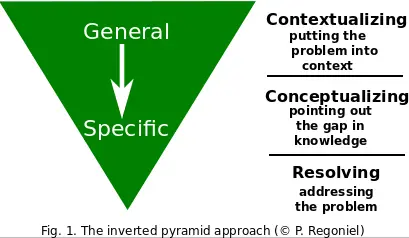

The following chart decomposes the above structure into more detail. While its structure is slightly different than the structure above – for instance, it treats the methods section as a part of the results section, rather than as a standalone section – it’s still useful, as it provides the narrative questions you need to address in each section of your paper.

(source)

The “gap” that the above chart mentions is the gap between prior approaches to a problem and your approach – that is, it’s the part that’s novel about your approach.

Let’s look at the sections of a paper in more detail.

Title and Abstract

Both the title and abstract of a paper should describe the contents of the paper:

- The title should do so in one phrase.

- The abstract should do so in one paragraph.

Both the title and abstract must be immediately understandable to readers who are unfamiliar with your work, and should be written in plain language. Remember, people browse abstracts to determine whether a paper is worth reading further; they won’t know the technical details of your work before they read it. You’ll be held to this standard in March, when you present your Quarter 2 Project at the capstone showcase – the audience will be a mix of faculty, industry partners, and fellow students.

You likely will only finalize the results and conclusions of your project towards the end of your project’s lifecycle. As such, you should only finalize your title and abstract at the end of your project. With that said, it’s a good idea to maintain a working title and abstract that you update regularly, just so that it’s clear to you what the focus of your project is.

In your abstract, spend roughly one sentence on each of the following four components:

- Contextualizing the problem. What is the world in which the problem lies? Why is this problem relevant?

- Reviewing gaps in prior approaches. What did prior approaches not solve?

- Clearly stating your project’s contribution to the problem. What was the “gap” that you closed, and how did you close it?

- Specifying relevant details to your methods.

To practice, read the following abstract, taken from Robust Learning from Discriminative Feature Feedback (Dasgupta & Sabato, 2020). Identify the sentences corresponding to each of the four components above.

Recent work introduced the model of learning from discriminative feature feedback, in which a human annotator not only provides labels of instances, but also identifies discriminative features that highlight important differences between pairs of instances. It was shown that such feedback can be conducive to learning, and makes it possible to efficiently learn some concept classes that would otherwise be intractable. However, these results all relied upon perfect annotator feedback. In this paper, we introduce a more realistic, robust version of the framework, in which the annotator is allowed to make mistakes. We show how such errors can be handled algorithmically, in both an adversarial and a stochastic setting. In particular, we derive regret bounds in both settings that, as in the case of a perfect annotator, are independent of the number of features. We show that this result cannot be obtained by a naive reduction from the robust setting to the non-robust setting

Introduction

The introduction sets the context for the rest of the paper. After the abstract, it is the first part of your paper that readers will read, and often the only thing they will read. Your introduction will start broad and become narrower and narrower as you add more detail.

(source)

There are three pieces to an introduction section:

An introductory paragraph. The first paragraph in your introduction will start by introducing the context in which your project is relevant. It will then state the problem that you’re trying to solve, and summarize some of your key results and their implications.

A literature review and discussion of prior work. Here, you’ll provide context on what has been attempted in the past in the realm of your problem. This will both set up the context in which your problem exists and shed light on why your approach is different.

A data description (this is a data science capstone, after all).

- If you’re in a data-focused domain, you should describe why the data you’re using will help address the problem at hand.

- If you’re in a methods-focused domain (that is, a domain in which you’re developing new methods), you should describe the kinds of data that your methods are applicable to. For instance, if you’re developing methods for using convolutional neural networks with graphs, you should describe why graph-based data is useful in the real-world.

Watch the video below, prepared by capstone TA (and former DSC undergrad!) Praveen Nair. It speaks more about writing titles, abstracts, and introductions. The slides used in the video can be found here.

Remember, your Quarter 1 Project Checkpoint submission will consist of both a report submission and code submission. Your report submission for the checkpoint should contain a working title, abstract, and introduction section. Watch the video above to help prepare!

Methods

This section often goes by different names, e.g. experimental design, and sometimes appears at the start of the “Results” section of a paper rather than as its own section (as we saw in the chart above). Regardless of its title, the purpose of this section is to describe the steps that you took to produce the results you’ll discuss in the following section. It should contain enough details for a reader to be able to understand what you did, without containing so much detail that it distracts from the storyline – leave ultra-fine details for the appendix.

If your project involves developing multiple models that are very different, you may want to dedicate a separate section to each one. This may apply, for instance, if you used two different approaches to solve your overarching problem, or if you used different models to label data and to train a classifier.

Results

In your results section, you should present data clearly without any interpretation. That is, readers of this section should be able to understand what you discovered, without having to read any conclusions that you made from those results.

As mentioned in the Guidelines section, you should strive to create figures that are self-contained. This means using informative titles, labels, and captions – don’t make readers guess anything. The contents of each figure should also be explained in writing. Make it clear in your text when the values and trends in a figure are particularly relevant to the exploration. Make sure to include hyperlinks in your text relevant figures (e.g. “see Figure 2”).

Discussion

In the discussion section, you’ll provide your interpretation of the results from the previous section. Here, you should describe how your results compare to prior work on the same problem. Are your results similar to what has been seen before? Are they significantly different? Why?

Be honest in describing the impact and applicability of your results, along with the limitations of your approach. There’s nothing wrong with your results having limitations; just be clear on what they are. Lastly, make sure to describe the possibilities for future work. How can someone else take your project and extend it even further?

Exercises

You will have to write the title, abstract, and introduction for your Quarter 1 Project and submit that as your checkpoint by the start of Week 6. As such, we’ve provided a few exercises below that will help you understand the role of the introduction section in a paper. You do not need to submit your answers anywhere, but you should still do them.

In an introduction, you need to give context as to why a problem is interesting. You must also clearly state the problem and scope in this context.

In one of the papers in your domain,

Specify the problem in concrete, testable terms and hypotheses. (To describe something in concrete, testable terms is to describe something in a way that is verifiable with math or code.)

Discuss the broader applicability of the results in the paper – what is the significance of the authors’ findings, both in the specified domain and outside of it?

Identify the most important figure/result in the results section of the paper, given the context provided in the introduction.

- Why is this result the most important – i.e., why is it the best summary of the approach the authors used to solve the problem?

- Is this most important result mentioned in the introduction? (Hopefully, it is!)